There Are Heroes and Villains: How Narrative Frameworks Enable Modern Disinformation

We think in stories, and that is being leveraged against us.

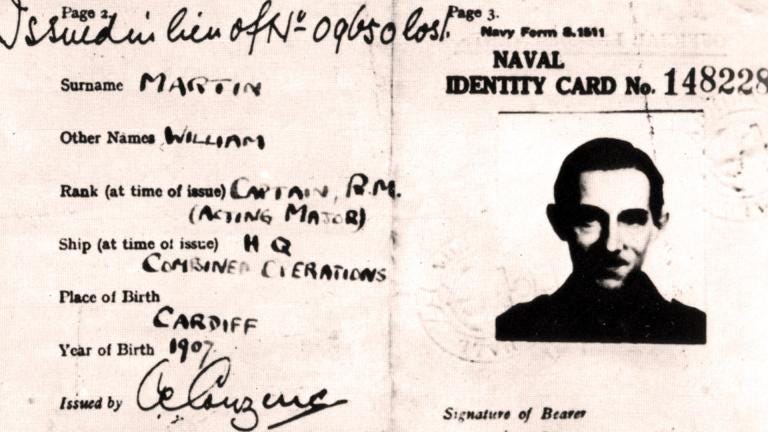

Operation Mincemeat.

What a name.

It sounds like a last-resort strategy born from wartime desperation. For those unfamiliar, Operation Mincemeat was a brilliant act of deception during World War II where British intelligence planted fake documents on a corpse to mislead the Nazis about Allied invasion plans.

Essentially, it was a lie.

And it worked remarkably well.

While Operation Mincemeat represents deception used for good ends, its success reveals something profound about how humans process information.

The operation worked because it didn't just plant false documents. It crafted a compelling story that played directly into Nazi expectations. German intelligence officers saw what they wanted to see: evidence confirming their existing beliefs about Allied strategies.

The British exploited this by portraying themselves as careless "villains" who had exposed their plans, while letting Nazi intelligence feel like clever "heroes" who had discovered the crucial secret. This story approach made the false information far more believable than any random collection of documents could have been.

Modern disinformation campaigns exploit the same vulnerability with devastating efficiency, but for far less noble purposes. Their power lies in activating narrative frameworks deeply embedded in human cognition, the heroes and villains dichotomy.

The Machinery Of Heroes And Villains

Humans don't just enjoy stories, we actually think in them. This isn't a quirk of modern culture but a fundamental aspect of how our brains evolved. For hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors survived by sharing crucial information through stories around campfires. Those who could understand and remember these narratives had a survival advantage.

From an evolutionary perspective, stories solved critical problems for our species. They allowed us to:

Pass down survival knowledge across generations

Build group cohesion and shared identity

Learn from others' experiences without personal risk

Make sense of unpredictable and threatening environments

Coordinate complex social behaviour

Our brains remain wired for narrative processing, automatically sorting random events into meaningful patterns with causes, effects, and central characters. When we encounter information, we instinctively try to fit it into existing story structures rather than analysing it as isolated data points.

This tendency offers clear cognitive advantages. Stories compress complex information into memorable formats, help us predict patterns, and facilitate social bonds. However, this same machinery creates specific vulnerabilities that disinformation architects deliberately exploit.

The heroes and villains framework stands as perhaps our most basic and powerful narrative pattern. At its core, this framework divides the world into:

Heroes: Those who embody our values, protect what we cherish, and represent our idealized selves

Villains: Those who threaten our values, endanger what we love, and represent what we reject

Crucially, we almost never cast ourselves as villains in our own stories. Each of us instinctively positions ourselves as either the hero or a supporter of heroes. Even those who commit harmful acts typically construct narratives where they're justified heroes responding to greater threats or injustices.

When disinformation campaigns craft stories, they exploit this self-positioning by creating frameworks. This is where the target audience can easily identify as heroes or hero-supporters battling clearly defined villains. This framework bypasses rational analysis by activating much older tribal thinking patterns. We process such stories not just intellectually but viscerally, as they tap into our fundamental need to protect our group against threats.

Information embedded in story form bypasses many of our critical thinking defences. Studies show that when we engage with stories, we enter a state where we're less likely to question claims, check facts, or notice logical problems. The more emotionally invested we become in a narrative, the more our analytical thinking fades into the background.

Beyond Simple Lies

At its core, effective disinformation exploits a basic truth about how our minds work. We don't judge new information on its own, but through our existing beliefs. This approach gives false information a very subtle but effective grip over our perception of reality.

The best disinformation campaigns don't just spread random lies. They build complete worlds of interpretation where various claims support a main story. Once someone begins thinking within this framework, even their view of basic facts changes.

This works because our emotions and group instincts come before our logical thinking. We first check if information comes from our side and supports our identity. Then we decide if it's true, but we make this judgment through the lens of what we already believe. Those who create disinformation understand this deeply, making content that triggers group loyalty before critical thinking can start.

The heroes and villains story comes naturally from these group foundations. After sorting information by loyalty, we naturally see those who agree with us as truth-tellers fighting against those who oppose us. This isn't forced. It's just how humans make sense of competing claims.

This explains why fact-checking often fails against well-established false beliefs. When someone has accepted a different way of interpreting the world, corrections don't register as neutral facts. Instead, they feel like attacks from the enemy group. The correction itself becomes proof that strengthens, not weakens, the false belief.

Who becomes the hero or villain isn't based on evidence or facts, but on which story better fits what people already believe. Once this hero-villain story takes hold, people reject solid information from "villain" sources while embracing dubious claims from "hero" sources, all while thinking they're making smart, independent choices rather than following a carefully crafted narrative.

Narrative Transportation And Cognitive Vulnerability

The power of stories to influence our thinking comes partly from what researchers call "narrative transportation". This is a mental state where we become deeply absorbed in a story. This concept, first studied by psychologists Melanie Green and Timothy Brock, describes how we mentally enter story worlds, often becoming less aware of our physical surroundings as we engage with the narrative.

Research shows several key effects of narrative transportation that make us vulnerable to story-based persuasion:

First, when we're transported by a story, we tend to lower our mental defences. Studies show we become less likely to argue against claims made within compelling narratives, even when those claims contradict facts we know. This happens because our mental resources are occupied with following the story rather than analysing it critically.

Second, emotional engagement amplifies this effect. Stories that make us feel strong emotions – whether fear, hope, anger, or pride – further reduce our critical thinking. These emotions serve as mental shortcuts, helping us decide quickly what to believe without careful analysis.

Third, identifying with characters in a story makes us more likely to adopt their perspectives. When we see ourselves in a "hero" character, we naturally align with their beliefs and values, often without realizing this shift is happening.

The heroes and villains framework acts as both a unifying and dividing force. It creates clear boundaries between groups: those who understand the "truth" (heroes and their supporters) versus those who either deceive or are deceived (villains and their followers). This boundary-making function helps people know exactly who belongs in their group and who doesn't.

This framework offers powerful social benefits that explain its persistence. By identifying with the hero side, people gain:

A sense of moral clarity in complex situations

Clear group membership and identity

The comfort of believing they possess special knowledge or insight

A feeling of purpose and meaning through opposing perceived wrongs

Social bonds with others who share the same narrative

These benefits explain why people cling to hero-villain narratives even when presented with contradicting evidence. Abandoning the narrative means losing not just a belief but group membership, identity, and purpose.

Disinformation campaigns exploit these vulnerabilities by crafting stories with clear heroes and villains that align with existing group identities. The most effective campaigns don't require people to change their core beliefs. They simply offer a narrative framework that organizes existing beliefs into a compelling story with clear good guys and bad guys.

The Narrative War Of The Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic shows how the heroes and villains framework can split our shared reality. What started as a health crisis quickly turned into competing stories, each with their own good guys and bad guys.

As the pandemic spread, we didn't just disagree about facts. No. We, as a collective, lived in completely different story worlds. Public health officials, scientists, sceptics, and politicians were all cast as either heroes or villains depending on which story someone believed.

These weren't just different views of the same facts. Each story created its own world where certain facts stood out while others disappeared. Whether masks helped or hurt, whether vaccines were safe or risky, whether lockdowns saved lives or ruined them. These answers seemed obvious to people in each story world, because the story itself decided which evidence counted.

The result wasn't just disagreement but total confusion and disagreement across the lines. People on opposite sides couldn't understand how others could be so "blind" to what seemed like obvious truth. This confusion shows the real power of the heroes and villains framework. It doesn't just change our opinions; it changes what we can see as real.

This pattern appears in many heated issues. The heroes and villains framework doesn't just add emotion to factual arguments; it fundamentally changes how we process information, which sources we trust, and what evidence we're able to see at all.

What this particular narrative war helps us understand is that the heroes and villains framework doesn't make us immune to its effects, but awareness gives us some defence. The key insight isn't that we should stop thinking in stories – that's neither possible nor helpful. Rather, it's spotting when we're being pulled into simple moral dramas that reduce complex realities to clear heroes and villains.

Real life isn't like the movies. The world rarely splits neatly into pure heroes and evil villains, but we frame it to be so. Most issues involve competing values, necessary trade-offs, and people with mixed motives. When information presents clear moral sides with no grey areas or complexity, that's not clarity. It's oversimplification.

The Complexity Helps

Understanding the heroes and villains framework doesn't make us immune to its effects, but awareness gives us some defence. The key insight isn't that we should stop thinking in stories, that's neither possible nor helpful. Rather, it's spotting when we're being pulled into simple moral dramas that reduce complex realities to clear heroes and villains.

Real life isn't like the movies. The world rarely splits neatly into pure heroes and evil villains. Most issues involve competing values, necessary trade-offs, and people with mixed motives. When information presents clear moral sides with no grey areas or complexity, that's not clarity.

Nope.

It's oversimplification.

The best approach to our complex information world involves developing what we might call story multiplicity. This is the ability to hold several different story frameworks in mind at once. This doesn't mean believing contradictory things, but understanding how different stories highlight certain parts of reality while hiding others.