This Week In Disinformation

30 November - 6 December 2025

🗣️ Let’s Talk—What Are You Seeing?

📩 Reply to this email or drop a comment.

🔗 Not subscribed yet? It is only a click away.

Across three continents this week, the information battlefield is still a constant. At its core, is how we relate to information.

In Washington, the Trump administration folded media intimidation into official state machinery, erecting a “Media Offender” portal on the White House site.

In South Asia, Pakistan turned artificial intelligence into a front‑line propaganda weapon, deploying deepfake generals to erode India’s military credibility after real‑world losses.

And in Taipei, Taiwan moved defensively, banning the Chinese social app Xiaohongshu after tracing it to mass fraud and systemic data failures.

Together, these stories show power consolidating around narrative control: governments redefining truth as loyalty, militaries faking speech to shape perception, and democracies severing links to hostile platforms before the next breach.

Trump Unveils “Media Offender Of the Week” and “Hall Of Shame” On White House Website

◾ 1. BLUF

The Trump White House has built a ‘Media Bias Portal’ on its official site, with a weekly ‘Media Offender of the Week’ and an ‘Offender Hall of Shame’ that names outlets, journalists and specific stories it brands as biased, false or misleading.

The portal is a structured campaign to weaken trust in critical journalism and to rally Trump’s base against selected media targets, rather than a neutral fact‑checking tool.

◾ 2. Context

Trump has attacked critical outlets as ‘fake news’ for years, but until now those assaults mostly lived in speeches, posts and one‑off rants.

He returned to office in a sharply split media environment, where many people already trust partisan sources over traditional news and treat arguments about accuracy as loyalty tests. That climate makes an official‑looking list of ‘liars’ feel less like a shock and more like the next logical step for committed supporters.

Trust in mainstream outlets is low, and many users now see news as screenshots and short clips without context. Studies of disinformation show that when leaders frame the press as hostile, their followers grow more willing to ignore corrections and to rely on their leader as the main source of truth.

The White House portal plugs straight into that gap, offering a ‘record’ of media wrongdoing under the cover of the presidential seal and a .gov address.

◾ 3. What Happened

On 28–29 Nov 2025, the White House rolled out a new ‘Media Offenders’ section on whitehouse.gov, branded with language about exposing misleading and biased stories.

The launch ran alongside Trump’s online attacks on coverage of a Democratic video aimed at service members and the 26 Nov shooting of two West Virginia National Guard members in Washington, D.C. The first ‘media offenders of the week’ were CBS News, The Boston Globe and The Independent, all tied to their reporting on Trump’s response to that video.

Under the weekly banner, the portal hosts an ‘Offender Hall of Shame’ and a searchable database of entries. Each record lists the outlet, named journalist, story description and date, and assigns tags like ‘bias’, ‘lie’, ‘malpractice’, ‘omission of context’ or ‘left‑wing lunacy’.

By early Dec 2025 the archive shows at least 10 posts dated 28 Nov and 4 Dec and several pages of results, covering dozens of stories and outlets including The Washington Post, The New York Times, Wisconsin Public Radio, CBS News, Associated Press, MSNBC/MS Now and Reuters.

◾ 4. Classification

This case is best seen as malinformation with clear disinformation tendencies.

The portal usually starts from real articles or clips, then strips nuance, assigns hostile labels and presents its view as fact without transparent proof, turning genuine reporting into a weapon against the outlets and people involved.

In some entries, the White House version of what a story ‘said’ appears stretched or distorted, edging into claims that may themselves mislead, though a full claim‑by‑claim audit is still lacking.

◾ 5. Tactics and Methods

The key method is to dress partisan attack content in the style of an official fact‑checking and record‑keeping tool. By hosting the portal on whitehouse.gov and speaking in the language of logs, archives and bias categories, the administration borrows the visual authority of a state database whilst avoiding the standards of evidence that genuine fact‑checkers use. This leans on a simple bias: people often assume government‑branded lists exist to help them, not to target opponents.

Using an official site also keeps the content beyond the normal reach of private‑platform moderation.

The tipline deepens this loop. It invites users to hunt for ‘biased’ coverage, send it in and later see their picks turned into official entries, tying grassroots outrage to state‑backed labelling. This pattern matches what research on harassment and dogpiling describes: a central signal from a powerful figure or body, then swarms of supporters taking part in targeted abuse, while the initiator claims only to be ‘informing the public’.

◾ 6. Implications

What stands out here is that an American administration has turned routine media‑bashing into a standing, state‑hosted targeting system. The weekly offender slot, the archive and the leader board together act like a radar and fire control network pointed at the press: they scan, lock and direct attention and pressure where the White House chooses.

In information‑operations terms, this shapes the home cognitive space by telling a slice of the public that mainstream outlets are serial violators and that the only trustworthy referee is decided by the publishing entity.

This move mirrors tactics used by governments that keep formal press freedom on paper whilst eroding it in practice. Naming journalists and outlets as ‘offenders’ on a state site, without clear standards or right of reply, lays groundwork for further steps, from access limits to regulatory pressure.

It also hands propogandists a vector of attack.

For defenders, the challenge is to treat this as an information‑operations problem, not just a political spat. Newsrooms, platforms and civil groups will need rapid support mechanisms for targeted journalists, clear public messaging that explains how state‑run blacklists differ from real fact‑checking, and better education for audiences on how to spot weaponised ‘bias’ labels.

◾ Sources

Media Offenders – The White House

Offender Hall of Shame Archives - The White House

Offender Hall of Shame Archives - The White House

A CALL TO ACTION: Submit “Media Bias” Tips - White House

White House Launches ‘Media Offenders’ Site and Tipline | TIME | Chantelle Lee

White House launches tracker to call out ‘media offenders’ | DW | Roshni Majumdar

Pakistan Using AI Deepfakes of Indian Generals

◾1. BLUF

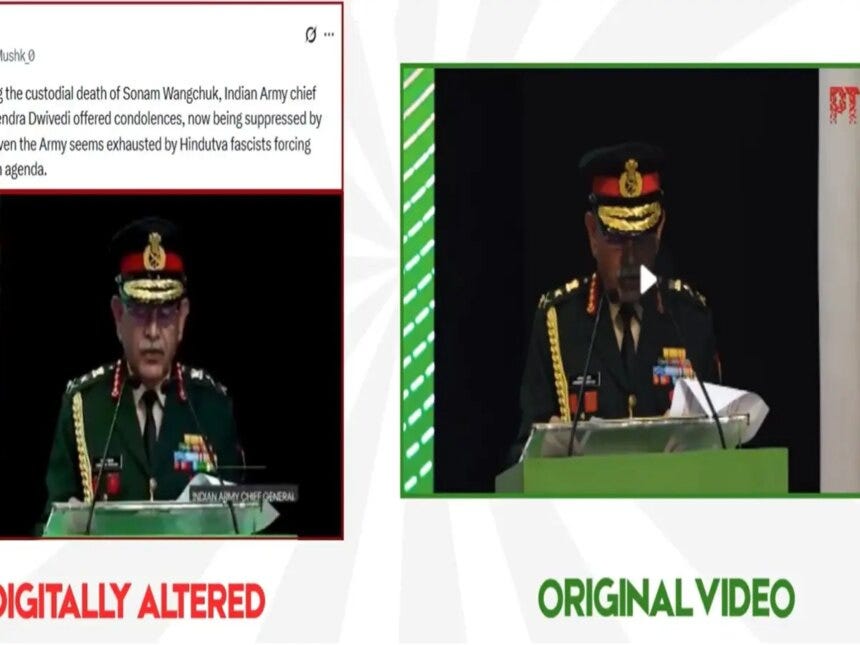

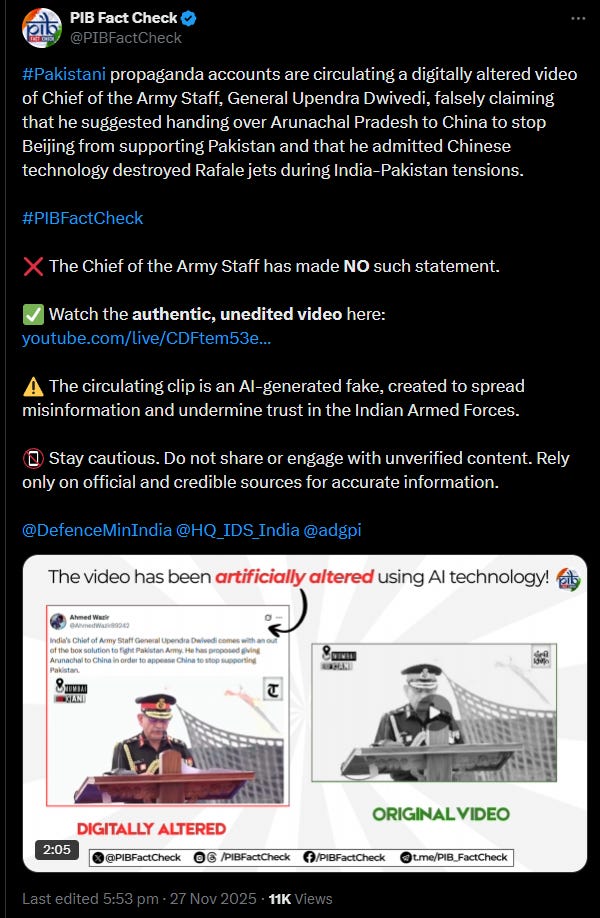

Between 24 and 29 Nov 2025, Pakistani-linked networks released AI-generated deepfake videos of Indian military leaders, including Admiral Dinesh K Tripathi and General Upendra Dwivedi.

These fabricated admissions of defeats and political interference in defence operations. Evidence points to ISPR-aligned actors seeking to undermine India’s military credibility.

◾ 2. Context

Tensions between India and Pakistan intensified through 2025, marked by Operation Sindoor’s naval engagements in May, subsequent airstrikes, and maritime alerts.

Pakistan claimed successes it failed to achieve militarily, turning to information channels for narrative gains. India’s Trishul exercises coincided with Bihar elections, opening avenues to portray defence matters as domestic politicking.

◾ 3. What Happened

Following the ISPR briefing on 04 Nov 2025, deepfakes emerged on 24 Nov 2025.

Accounts based in Pakistan overlaid Admiral Tripathi’s image with synthetic audio that blamed government policy for Sindoor losses; DAU analysis confirmed full fabrication.

By 28-29 Nov, General Dwivedi seemed to dismiss Trishul as electioneering, and Air Chief Amar Preet Singh to concede S-400 setbacks. Each linked to local IP addresses and bot activity, with one related video gaining 40 million views in 24 hours.

Over 200 pro-ISPR handles pushed content across X, YouTube, and WhatsApp in Hindi and English. NDTV footage suffered alterations into three variants by 24 Nov, alongside a false defence advisory flagged by PIB. Official units debunked materials within days, identifying 99 per cent synthetic elements, though initial circulation preceded removals.

◾ 4. Classification

This is disinformation.

Claims of operational failures and political overrides lack foundation in records or corroboration, disproved by forensic tools. Patterns of timing after ISPR statements, account clustering from Pakistan, and election-targeted angles indicate coordinated deceit, not inadvertent error.

Sustained deployment across formats and leaders, despite counters, underscores intent to disrupt perceptions.

◾ 5. Tactics And Methods

Video format carried authority; deepfakes of known faces provoked stronger reactions than static claims. X enabled quick amplification through emotion-driven algorithms, while WhatsApp bypassed oversight for local networks with posts timed for 19:00-22:00 IST peak use. Networks synchronised releases, creating organic appearance

◾ 6. Implications

Methods match Pakistan’s post-defeat patterns, as in 2019 Balakot, but AI adds pace and cover. ISPR connections signal capable infrastructure that is likely to grow.

Amid Operation Sindoor fallout and polls, the approach tested India’s information posture without physical escalation.

◾ Sources

How Pakistan used AI deepfakes after failing to counter India during Operation Sindoor | YouTube | RNA

Doctored Missile Launches To Deepfakes: How Pakistan Is Using Synthetic Media to Target India | The Daily Jagran |

Pakistan Utilizes AI-Generated Deepfake Videos to Spread Misinformation Against India | SSB Crack | NewsDesk

Tracing Pakistan’s Assembly Line for Anti-Trishul Propaganda | DFrac | Aayushi Rana

Pak-Linked Fake Videos Surge Online | WION News | YouTube | WION

Taiwan Bans Xiaohongshu (Rednote) Social Media App

◾ 1. BLUF

Taiwan banned the Chinese social media app Xiaohongshu, also known as Rednote. on 04 Dec 2025 for one year after it linked to over 1,700 fraud cases causing losses of $7.9 million USD, failed all cybersecurity benchmarks, and refused to aid police investigations.

Taiwan’s Ministry of the Interior drove the action (high confidence), driven by fraud protection and security needs amid tensions with China (moderate confidence in geopolitical intent). This sets a precedent for digital sovereignty, forcing 3 million users to adapt and signalling tighter controls on Chinese platforms that evade local laws.

◾ 2. Context

Taiwan faces a surge in online fraud, with Chinese apps like Xiaohongshu serving as conduits for scammers targeting its 23 million citizens. These platforms draw users with lifestyle content but harbour risks from lax oversight across the Taiwan Strait. Since 2019, Taiwan restricted apps like TikTok on government devices, citing data leaks to Beijing, yet private adoption grew to millions amid economic ties with China.

Furthermore, China claims Taiwan as its territory, using digital tools for influence and economic pressure. Fraud cases spiked in 2024, coinciding with Beijing’s grey-zone tactics. Xiaohongshu’s 3 million Taiwanese users created a ripe channel, as scammers exploited trust in viral posts promising quick riches or fake deals.

◾ 3. What Happened

On 04 Dec 2025, Taiwan’s Ministry of the Interior announced a one-year ban on Xiaohongshu.

The National Police Agency documented 1,700 fraud incidents since 2024, with losses hitting 247.7 million Taiwanese dollars ($7.9 million USD). Scammers used the app for fake investment schemes and phishing, luring users via influencers and shop links.

The Ministry acted after Xiaohongshu stonewalled cooperation. Police sought user data and transaction logs, but the Beijing-based firm cited Chinese laws blocking handover. A National Security Bureau audit found the app failed 15 cybersecurity tests, from data encryption to vulnerability patches. This includes spying and sabotage.

◾ 4. Classification

This incident counts as factual.

Taiwan intent centres on citizen protection and platform accountability, though moderate confidence ties it to anti-China posturing given Beijing ownership and strait tensions.

◾ 5. Tactics and Methods

Taiwan chose a blunt ban over fines or talks, fitting a vulnerability: Chinese firms dodge foreign rules via sovereignty shields. This sidesteps drawn-out lawsuits, instantly neutering the threat.

Effectiveness has been observed in speed. Past TikTok curbs cut government risks without mass uproar; this scales that playbook to civilians.

◾6. Implications

Taiwan’s move breaks new ground by wedding fraud stats to cyber dreads for a consumer app ban.

Scale matters: 3 million users equals 13% of Taiwan, forcing a rethink on China-tied tech. Tactically, it mirrors NATO cognitive defence plays as this block vectors before influence flows, without firing a shot.

Patterns echo Beijing’s digital exports elsewhere. TikTok bans in India (2020) and US probes show the template: audit, expose, sever. Xiaohongshu fits China’s app arsenal, blending commerce with sway.